Upcoming Joint Photo Show – Miami Art Works Gallery

Making front page news!

Making front page news!

This was originally published in Sucient Magazine ten years ago, but has since mysteriously been removed from their archives, so I am reposting it here.

What do you do with your faith when your religious leader is found dead, sitting in chair surrounded by a pool of his own piss in a luxury hotel room that is “strewn with pills and empty liquor bottles?” How do you keep your faith safe when your spiritual shepherd could not save himself from his own substance abuse — especially when it was your money that had been funding his addictions? A. A. Allen’s body was found in the San Fransisco Jack Tar Hotel where he had died of acute alcohol poisoning during a particularly heavy drinking and pill-popping binge in 1970. He was buried on the grounds of the Miracle Life Fellowship International Bible School in Miracle Valley, Arizona. Allen had originally founded the school in 1958. With a long and sordid history, the Miracle Valley compound is slowly falling into ruins while a few devote followers struggle to realize their dream of restoring it to its former glory.

Driving down desolate Arizona Highway 92 with my son, there was little to see other than open dry grassland stretching in all directions between distant broken mountains. This section of Highway 92 is less than three miles from the Mexican boarder. My son was thirsty and asked to stop to get something cold to drink. We stopped at a rundown liquor store at the intersection of Healing Way and Highway 92. Just south of the liquor store, the Prayer Dome of the Miracle Valley Tabernacle stood, surrounded by tall grass and a number of rundown buildings. The roof of the Tabernacle looked as if it had been violently ripped off to expose the great hall that had once been filled with fervent believers.

I pointed to the complex and told my son, “We’re going in there.” My son smiled. We had already trespassed in abandoned houses, a church and heavy mining facilities earlier in the day, so it seemed natural that we would go into these abandoned buildings as well. Still, there was something foreboding about Miracle Valley.

Walking along Healing Way beneath the broken bible school sign and climbing over the barricade, we couldn’t help but feel the presence of the thousands of people who had come here before us. The complex had been a Mecca for Allen’s followers and for those hoping to join Allen in his crusade to spread the word of the Lord. Seeing it in ruins made you consider the universal question of what is real and what has meaning — Miracle valley had been meaningful and significant to so many believers in the past, but now lay dissolute and in ruins.

The first building we came to was the cafeteria and meeting hall. The main doors were locked tight, but when we went around back we found a door that had been jimmied open. The kitchen was partially stocked and looked as if it could be ready for service without much work, as if the workers had dropped their utensils and departed unexpectedly and without notice. Inside the main room, a large group of Gothic-style high-back chairs sat neatly arranged for a large gathering. It was unclear if the participants had just left — or if they would arrive at any moment. The room was decorated for a fall celebration.

Next we found a school building. In the classrooms the chairs sat as if the students had stood up and left for a fire drill, but upon leaving had been lost to some great unknown apocalypse — never to return. The emptiness and loneliness of the chairs was heartbreaking. The lives of the occupants seemed to hang on the edges of the all the furniture that their hands had last touched on their way out. On some chalkboards lessons remained untouched, as if the teacher had just put down their chalk before following the students out the door.

Dormitories were left a tumbled mess of personal belongings, alarm clocks, cleaning aids and furniture. Looters had set fire to a few rooms, and smoke damage added to the mood of desperation and abandonment. Many people had shared these rooms and passed each other socially in the halls. As trespassers, it was hard not to fear that someone or some group of armed men was hiding inside one of these rooms.

Fear is justified — this region is right on the Mexican border and known for drug smuggling, human trafficking, violence and murder. The Miracle Valley compound could easily be used by cross-border smugglers. Gunfights frequently explode on the the nearby highway between innocent passers-by and illegals attempting to steal their cars. Competing drug smugglers often resort to murder to settle disputes out in the lawless desert. Minute Men hunt illegal boarder crossers under the guise of “protecting U.S. sovereignty.” As we pushed our way into every unknown room we felt as if we were members of an elite swat team armed only with cameras.

Growing up in a Catholic family, I had never listened to any of A. A. Allen’s numerous daily radio and TV broadcasts. I wasn’t aware of the Miracle Magazine that he published monthly to highlight the many modern-day miracles attributed to him. I had no idea that I was going to stumble on the remains of Miracle Valley when I took my nine year old son on a short overnight father/son outing for my birthday. We went to explore ruins around Bisbee, Arizona. My boy likes old mining sites and abandoned buildings and has dreams of finding a forgotten chest of gold in a collapsed mine shaft or an old suitcase stuffed full of gangster cash in an abandoned building.

Who doesn’t dream of a happy miracle that will change their life forever? Allen was one of the few ministers to talk about God’s ability to perform “financial miracles” — generally more Judaic in tradition than Christian (Prayer for Parnasa vs. “blessed are the poor”).

A.A. Allen wrote in his booklet, Power To Get Wealth. How You Can Have It! that the key to financial success could be found in Deuteronomy 8:18: “It is He that giveth thee power to get wealth.” Allen added, “Christ came to do away with the works of the devil, and one of the works of the devil is POVERTY!” Capitalizing on this promise, Allen began selling “prosperity clothes” which were anointed with his mysterious “Miracle Oil.” Allen sold these handkerchiefs for $100 (a very large sum in 1958). Allen promised “Just as soon as I receive your letter with your gift of one hundred dollars… I will send you a new handkerchief over which I have prayed for your prosperity,” and he promised to forever change your fortune with this act. Allen said he could command God to “turn dollar bills into twenties.” No matter how you do the math, you’d be a fool not to purchase one of the these prosperity handkerchiefs, right? After you turned just five dollars into twenties, everything else was free money!

The miracles Allen promised didn’t stop with financial success, his TV commercials went on to claim, “See! Hear! Actual miracles happening before your eyes! Cancer, tumors, goiters disappear! Crutches, braces, wheelchairs, stretchers discarded! Crossed eyes straightened! Caught by the camera as they occurred in the healing line before thousands of witnesses.” Allen often matched his wild promises with wild style, wearing outlandish outfits such as a lavender suit with white patent leather boots. What the commercials didn’t tell you was that Allen’s hired “goon squads” violently prevented all independent photographers and reporters from documenting or testing the validity of his claimed miracles.

The concept of faith-healing is interesting on a scientific basis. Even if Allen was guilty of questionable practices, science and statistics would suggest that, given the vast numbers of people who attended his revivals, many would actually find the “miracle cures” that they came looking for. Current research has shown that even when using mainstream commercial pharmaceuticals, more than 50% of of their effectiveness comes from the placebo effect. Our bodies work in mysterious ways, especially when we have strong faith and belief in the cure. It begs the question, “What does truth matter when even a lie can heal you?”

Allen started out as a preacher in the World Assemblies of God Fellowship in 1936. After attending an Oral Roberts tent revival in 1949, Allen’s calling to spread the “miracles” of the Lord was awakened. Shortly after witnessing Robert’s revival he founded A.A. Allen Revivals, Inc. This gave him both tax exempt status and put him in control of all financial gains from this venture. Then he went on the road in earnest pushing his Healing Revival Campaigns across America. In 1955, Allen took the boldly entrepreneurial step of purchasing a large expensive tent — something he could not afford — that could accommodate over 10,000 people. Allen had faith in his own success.

In this same year, Allen was arrested for driving drunk in Knoxville, Tennessee. He was already plagued with rumors of his alcoholism. This event was the last straw for the Assembly of God organization who then pushed him to resign from their ministry. During this same time, Allen also resigned from the Voice of Healing association in whose magazines he had been a regular contributor since 1950. When his drinking became too much to hide, Allen pulled out of all organizations that he had initially looked to for support. As an independent agent he began to rely solely on his growing popularity and his own organization in which he held absolute financial control.

While Allen jumped bail on his drunk driving arrest, in Miracle Magazine he claimed that the charges were nothing but “a trick of the devil to try to kill his ministry.” Allen and his supporters claimed that all the drinking and corruption charges lodged against him were nothing but malicious slander. For governments and religion movements, keeping yourself on a war-footing increases solidarity amoungst your ranks. Examples of this can be found in Americans fighting their “War on Terror,” politicians in the former Soviet Union at war with everyone within and without, followers of Jim Jones and the People’s Temple fleeing to Guyana and David Koresh, leader of the Branch Davidians barracading himself and his followers into their Waxo, Texas compound — all relied on followers coming together to fight against what were perceived to be common enemies, real or imaginary. All allegations of corruption and misdeeds by Allen were discounted as persecution of not only Allen, but against all his supporters and followers as well. There are currently numerous websites devoted to conspiracy theories that are meant to debunk the official accounts of Allen’s life and death, but I am not trying to untangle all of these here.

The land that Life Fellowship International Bible School was built on was given to Allen in 1958 by Urbane Leiendecker, a young rancher. God reportedly spoke directly to Leiendecker as he sat alone in his pickup truck one night looking up at the stars. God told Leiendecker, “My son, from this place the Gospel shall go out to all the world…with signs, wonders and miracles.” A short time after this visitation and while Leiendecker was attending the 1958 Great A.A.Allen Winter Camp Meeting in Phoenix Arizona, God returned. During the morning prayer meeting, God again spoke to Leiendecker saying, “This is what I have asked you to do with your range! This is the purpose for which I have ordained it and told you to give it to Brother Allen.” Within days, A. A. Allen Revivals, Inc. was named as the sole owner of Miracle Valley.

After Allen died, the property changed hands many times. First it went to Reverend Don Stewart. After taking charge, Stewart was immediately hit with allegations of embezzlement and pocketing offerings from the revivals by Allen’s brother-in-law. Stewart moved up to Phoenix and tried to sell the school. He gave up in 1975 and leased the college to the Hispanic Assemblies of God organization for one dollar a year for twenty years, essentially giving the property away.

This new group turned out to be somewhat militant in actions and beliefs and preached what locals referred to as “anti-white doctrine.” The group had repeated hostile and violent confrontations with neighbors and utility workers. In 1982, law enforcement was called in. An armed standoff ensued that ended with two group members and one deputy shot dead. In the same year, an arson fire caused substantial damage to the administration office and a large warehouse on the property.

Stewart received a one million dollars insurance cash-out settlement from the insurance company. To avoid a prolonged legal battle with the Hispanic Assemblies of God organization (who still held a 20 year lease on the property), Stewart gave them the property as-is with the agreement that they would maintain a bible school on it for an additional twenty years. After receiving his one million dollars, Stewart walked away with more money than he probably could have gotten though any legitimate sale. The arsons were never caught.

The Hispanic Assemblies of God organization occupied the premises for precisely twenty years after receiving the property from Steward, thereby honoring their legal commitment. Then, in 1999 they sold the complex to the Harter Ministries who began teaching classical Pentecostal theology. They found it hard to make money teaching classical theology. Within ten years, this new bible college was destitute and unable to meet expenses. In January, 2009, banks foreclosed on the property and it was vacated by force of court order. This explains the Thanksgiving and Christmas decorations strewn throughout the compound — traces of what would be the final celebrations in Miracle Valley.

What did the devotees feel while celebrating their last New Years in the complex? Did the weaker in the group sneak off to buy liquor across the highway? Did they huddle together praying for a financial miracle that would save their school? Were they making plans for what they would do if the school was lost? Or did they find denial in their faith?

Allen is quoted saying, “Again and again, when my head was splitting and my frayed nerves let me shake visibly with a ‘hangover’, I promised myself I would never go on another again. But when night came, I was right back there…the life of the party! A confirmed drunkard!” After dedicating his life to spreading the Lord’s Word, Allen said, “No more dances! No more liquor! No more cigarettes! Desire for them had vanished, and a new joy and peace had taken their place.” What had filled his new life was money, power and a devoted following. Life on the road, fancy clothes, throngs of fans — it all had to be exciting.

In the adminstational offices, the ghost of Allen still lingers. You can imagine not only the financial power Allen had at the apex of his career, but his isolation. What did Allen think when he sat up alone at night? How did he deal with his personal crises of faith? Looking out through the north facing windows in the Dome of Faith at night, the lights of the liquor store beckon from across the field. Did Allen send a faithful assistant out for liquor when the pressure of being A. A. Allen became too great to bear, or had he successfully kicked his alcoholism as he claimed (despite the fact that after his death, the coroner concluded following a 12-day investigation and autopsy that Allen died from “liver failure brought on by acute alcoholism”)? Does it even matter anymore?

God is reported to have told Allen, “I say unto thee I have ordained this place [Miracle Valley] and if thou wilt trust me, there shall no evil befall this place. There is no power that can destroy that which I have ordained. If thou wilt leave that I am the God of all flesh, that I am the same yesterday, today, and forever, no evil shall befall this place, no destruction, because the hand of the Lord is upon this place and surrounding this place. I shall protect it from all the powers of evil and all the powers of man, for I, the Lord, am the power of all powers. There is no power but of me, saith the Lord, and I shall protect, I shall keep, and I shall save throughout the Millennial Age, saith the Lord.”

After my son and I emerged from the last building, we heard the sounds of glass shattering and other materials being smashed. The sun was going down, and darkness descended around us. We rushed through the central grounds of the compound and saw two carloads of teenagers wielding sledgehammers, smashing windows and breaking down doors. We were done exploring and didn’t want to confront them. As we quietly walked out toward the main highway where our car was parked along Healing Way, we heard sounds of continued destruction punctuated by riotous laughter. No one was protecting Miracle Valley on this night.

So taking a somewhat winding road to get here, and shooting everything between small format film (Minox and 110) and large format (6×9 120 and 4×5”), I am back to shooting 35mm b&w film in a big way. I’ve always contended that 35mm wasn’t the best film format, but that it probably was the best compromise format optimized for practicality, size, and quality. While I was concentrating on my Leica IIIf and Red Scale Elmar, this camera developed a capping issue (even though I recently had new curtains installed in it). After I sent the camera in for further adjustment, a pushed ad from usedphotopro.com (highly recommend!) popped up hawking a Kodak Retina Ia for $37 with free shipping. Since I’ve also been getting back into biking, a quality small inexpensive pocket camera seemed like a good thing to add to my collection, so I ordered it.

It’s not perfect, but after cleaning the lens and viewfinder it’s been a mostly reliable camera. Quality of the photos are easily on par with the Leica–no surprise since both are products of fine German engineering and optics. Unlike my Kodak Retina IIa, the Ia has no rangefinder, but instead is only scale focusing (guess), but stopped down, I haven’t spoiled a photo yet because of bad focusing. Also, I am finding the simple viewfinder without integrated rangefinder lends itself to concentrating more on composition. This made me realize that one of the first things I was taught when I started studying photography–that you needed an SLR for serious work–was definitely wrong. The reason given (aside from no parallax issues) was that you were looking through the taking lens. Unfortunately, as a young student, composing through a wide open lens with shallow depth of field made everything basically look better and almost magical while composing, but in ways that didn’t automatically transfer to the prints you were going to make in the end. The distracting bits that were hidden in the blur were often way more evident in the print, or on the other end, important details were less sharp than you expected. All of this works itself out with experience, but the same can be said for a rangefinder camera.

There are many different types of shooting, and when I was shooting more portraits back then, I would use long lenses with fairly wide apertures for a classic shallow DoF look, but for maybe the last 10 years, I’ve shifted much more toward deep focus landscape/scenic photography, so a simple Galilean viewfinder gives me a much better view to compose from than that of a shallow DoF SLR with a fast lens. Parallax is only an issue with close focus, so rangefinder/viewfinder cameras really are not an ideal choice if this is what you need to do, but I find this limitation, more often than not, forces me to take better photos because I retain context.

The old adage (attributed to Robert Capa), “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you aren’t close enough” can be taken to extremes and when you put a nice macro lens on my camera, I often end up getting closer and closer and ending up with mostly (interesting?) abstracts. Nothing wrong with this, but personally, I’m looking to build my abstractions and art on top of and from contextual reality. Kind of similar to my personal philosophy for getting by in life—don’t deny reality, but find the magic within it and in spite of all the imperfections.

One thing I noticed getting back into film work is how much film prices have increased over the last ten years that I have shot (color!!!) digital exclusively. Tri-X is now nearly $10 a roll for a short roll and this is starting to seem prohibitive to me so I started looking for alternatives. In medium format, I had been primarily shooting Fomapan 100 (mostly because it is the only film I can read the numbers through a ruby window) and I was getting fine results. Fomapan is a fine film, but for the speeds, it is a bit grainy from what I’ve seen. Then I read about Kentmere Pan 100 which is made by Ilford (really!) and decided to give it a go. It took a few tweaks from what is published in The Massive Developer Chart before I was happy with the results, but now I am consistently getting stunning results using it in Tmax Developer 1:9. I’m finding Kentmere Pan 100 for around $75 per 100’ roll, which ends up being less than $4 per roll when I bulk load. With my quality Russian made steel re loadable cartridges, the added effort is minimal. The new plastic ones from Adorama and B&H are garbage.

When I was younger, I always shot 400 speed film, “just in case” I needed those two extra stops for handheld shooting, but now, I feel the much finer grain that can be had when shooting 100 speed film is much preferable. It doesn’t mean I can’t appreciate the aesthetics of Tri-X in D-76, it just means that what I’m shooting now benefits from the finer grain and smoother tonal gradients from a finer grain film. I also shoot much less candid “people shots” and prefer stopping down and using a tripod for my low light work instead of trying to get away with a 1/15th or 1/30th low light handheld shots. For most people, even 1/60th handheld, while “acceptable,” is really not ideal for image quality. I believe Ansel Adams once said something like, “If your lens isn’t sharp enough, buy a tripod.”

Another reason I am loving these little Retina cameras, other than size, absolute quality, and low cost, is because they are one of the few pocket 35mms that are fitted with a 50mm lens. By the end of the 60’s, pretty much every quality fixed lens small camera had a 35mm lens (Contax, Minox, Olympus, etc.)! This is fine, and I know many people prefer them, maybe more than those of us who like a 50mm field of view, but for me, I find a 50mm lens ideal for a one focal length solution. 35mm lenses always feel awkward and sloppy to me.

Aside from the rangefinder versions of the Retinas (II, IIa, IIIc, and IIIC) which have an f2.0 taking lens and an integrated rangefinder, all the “lessor” models have some form of a Tessar lens (Kodak Ektar 50/2.8 or 50/2.8 or 50/3.5 Schneider Kreuznach Zenar lens are the most common). Tessar lenses are known to give very good results when stopped down a bit and by f/8, I cannot see any corner lack of sharpness or vignetting at all on images from any of my Retinas.

Tessar lenses just have a wonderful classic look to them. They aren’t magic, but instead just look right to most people. Perhaps it’s the fact that many many famous photos have been taken with Tessar lenses. Many early press corps used Rolleiflexs or Speed Graphics fitted with a Tessar lens and while most people don’t look for lens signatures, they do seem to subconsciously notice them. We see something enough and it becomes something we expect to see. For 60-70 year old lenses, these are quite fine performers.

Aside from the Kodak Retinas, other pocket 35’s with a 50mm lens include the Barnack Leicas when fitted with a collapsible Elmar lens, and other folding cameras like the Balda Baldinette, Welta Welti, and Voigtlander VITO series of cameras. There are others as well, but somehow, the German made Kodaks excite me the most, and except for some of the rarer ones, all are basically the cheapest. The Retina Ia that I have represents about the cheapest Retina you can get, rarely going for much more than $50 for a fully working and near mint copy.

Regarding pocketability, life changes when you have a real camera with you at all times. I don’t like walking around with a heavy full sized camera slung around my neck at all times. It gets in the way and it actually starts hurting my back after a couple hours, but shoved in a pocket, my Retina never gets in the way and is always ready to capture something that strikes me as remarkable. Someone in one of the forums I often post my photos to commented that they liked how I “document the things everyone passes by everyday, but doesn’t notice.” I don’t really think I’m a documentarian, but more an artist creating something from what I see, but since photography is rooted in (trapped by?) reality, I think it is more seeing something that offers potential to convey an emotional message and capturing it in the best possible way. You don’t have to travel around the world to do this, you can even find things to shoot in your own back yard. The biggest challenge is translating the emotional content onto the film while managing all the imperfections and awkwardness of reality.

Depending on how you look at it, all Retina cameras are fully manual, even if it is one of the newer models with a builtin selenium meter, which is good, because it is always a crapshoot whether an old selenium meter will still be functional. It also avoids the problems associated with specialty or impossible to find batteries. I could say I was a purist and won’t shoot auto exposure (only) cameras, but I’m not. If someone like Minox had made a camera like a GL with a 50mm lens, I would love to shoot it. Even though you dream up situations where the focal length limitation would impact what you’re able to shoot, one of my fundamental thoughts regarding photography is, “There are infinite photos to take, so don’t worry about the ones you can’t take.” Focus on what you can create with the gear at hand.

For those that have noticed that I haven’t been keeping up on my blog here very well, part of that is because I have gotten much more active on Instagram. If you are over there much, check me out and follow at http://www.instagram.com/markhahn_art_music/. I am very actively posting there (almost everyday).

When my Leica IIIf developed a shutter problem and needed to be sent in for adjustment, I needed a new small pocket camera I needed something to quickly replace it with. Since most modern pocket P&S cameras come with a 35mm lens and my preference is a 50mm lens, it means I pretty much have to go back farther in time to get one. While I have a beautiful Retina IIa, it seems too nice to bang around when I’m out on my bike (something I also realized about my Leica!), so while I was deciding what to do, facebook’s wonderful AI pushed an ad for a nice user grade Retina Ia. Very much like my IIa, but smaller and with a slower lens, and for $37 shipped, hard to turn down. Then an hour or so later, I get another pushed ad, this time for Ib that looked pretty much close to Mint- to my eyes, and even though I was never a fan of the larger later series Retinas with a rangefinder, the Ib just looked cleaner to my eye, so I reluctantly ordered this camera as well! Both came from usedphotopro.com where I’ve gotten good deals in the past (so yes, no connection, but giving a recommendation for a business I’ve been satisfied with!).

Other than a few dust speck in the otherwise pristine lens, and a crisp shutter working at all speeds, the only issue the camera had was a very fogged viewfinder. I went online to get some instructions how to tear it down and clean it, but couldn’t find anything, so I’m putting this up for the community in case someone else needs to do this.

You can see from the screw heads that someone has had this camera open sometime in the past. Everything is probably working much too smoothly to expect it was not touched in the 60+ years since it was first manufactured anyway.

First step in getting to the viewfinder is removing the top cover. You start by removing the rewind knob.

Use a nonmarring object to hold the film pin and unscrew the knob. It just comes off.

Next, remove the two cover screws that are under the rewind knob.

Next, remove the last cover screw from the end of the cover.

The cover simply lifts off at this point. You can clean the viewfinder lenses in the cover without removing them.

The brightline pack is in the middle of the camera top. The elements are held in place with a slide on cover.

This cover just slides off when you push it forward.

You simply slide the front and rear packs out of the frame, noting the stacking order.

There are two glass slides with mirrored bright lines and a forward lens element. Mine had so much haze it took two tries with lots of Windex to get them all clear. I think it came from the grease on the wind mechanism that is under the same cover outgassing over the years.

After you get all your optical surfaces clean, you simply restack the pieces and slide back into place. It took a few tries for me on the forward stack and they went flying onto my work surface at least once, but once they are in place, all is good. Slide the cover on and insure you didn’t get a finger print on any surface while reassembling.

Putting the cover on is just the reverse of how you took it off.

While the bright lines aren’t a bad thing, they aren’t really that useful since they are basically right at the edges of the viewfinder anyway, but I guess it is a step up from the simple viewfinder in the Ia.

In general, the camera is a nice step up in most ways from the Ia, with many subtle refinements, but a little bigger camera overall. The only annoyance is the locked coupled EV system which makes it difficult to change settings for varying lighting situation. I guess they thought in constant light, you might want to shift your shutter speed or aperture while holding the same exposure, but with the limited settings, this is practically useless. Since you can’t select a shutter speed of 1/500th if the camera has already been advanced and I prefer to avoid handheld shots at or below 1/60th, it leaves me two shutter speeds and apertures to shift between, and the difference between shooting at f8 and f11 isn’t a big enough deal to warrant locking up my whole camera for! In reality, you basically just get used to having to set the shutter speed first and then twiddle the aperture lever so it doesn’t drag the shutter speed with it while changing it.

All in all, this is a very refined and beautiful camera to hold and to use, and apparently the hipsters haven’t gotten hip to them yet and the prices are still very reasonable. Consider picking one up.

When Kodak released their new 110 pocket Instamatic film they produced a wide range of cameras to support the format. They ranged from the simple inexpensive fixed everything snap shot cameras to the high end cameras with fast f2.7 sharp lenses which were very expensive for the time (over $700 in today’s dollars!). The highest end ones had an integrated rangefinder. In ’72, this was the pocket Instamatic 60 which was replaced a few years later with the Trimlite 48 (shown above).

After 50 years, it is common for these rangefinders to have gone out of adjustment. This may potentially be from stress relaxation of the all bent parts that the camera uses, but doing deep searches on the internet, I was unable to find any reference on how to adjust them.

The first thing you have to do is remove the top cover. To do this, you need to take your jeweler’s screw driver and find somewhere along the edge of the cover to start lifting it off. The cover has positioning tabs on both ends and some glue to keep it on. The glue will probably have gone brittle so won’t cause much problems, but once you find a point where you can start lifting the cover off, just slide it along to loosen the cover until it comes off (without marring or bending it!).

Once the cover is off, you can see the top of the camera workings. Deep in the access hole (shown) is a flathead screw that adjusts the lateral movement of the rangefinder.

While the first photos shown are of the Trimlite 48, you can see below that the pocket Instamatic 60 is essentially the same camera. Same hole and same adjustment.

What I do then is to measure out 15′ from a small light source, set the distance scale to 15′ and adjust the rangefinder to show 15′. After adjusting to 15′, I then confirm that the rangefinder is good for 4′ and 30′. Everything else is fine at that point (within the tolerance of the scale anyway). For small formats, precise focus isn’t as important as it is for larger formats.

The only problem left is that (I cannot find) there isn’t a vertical adjustment for the rangefinder, so even once it is setup for accuracy, there will likely be a vertical offset. If anyone finds a way to adjust that, please let me know and I will update this page!

Regarding the rangefinders, I think they are very bright, but others want brighter, so they darken the center of the viewfinder to make them appear brighter. I already find the brightness a little distracting for composing images (preferring separate VF and RFs ala. Leica Barnack), so I might consider going the other way and covering up the rangefinder window with a small piece of black tape so it went away until I really needed it. Really, I’ve got a pocket Instamatic 50 in my pocket which is exactly like the 60 without a rangefinder at all.

Aside from the Trimlite 48 being pretty ugly (IMO), the benefit it has over the 60 is that it reads 400 speed film. The 60 only works with “slow speed” films. This could be a big deal depending on what you want to shoot. I mostly shoot in good light. But since you never get something for nothing, what you lose with the 48 is a cable release socket, so if you want to do tripod work, the 60 is by far the better choice.

My film student son had to do a quick demo video using reflected light, so he chose me with my large format camera on the spectacular vintage Tilt-All tripod for the subject matter. I think it’s really well done. All handheld with a manual focus lens.

"Read Dial" Leica IIIf With "Red Scale/Diamond" Elmar Lens Both From Around 1952

In conversations on social media and in real life, I’ve been discussing how I’d like to simplify my photographic life and only settle on one camera. When I started as a photography student at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I only owned a basic Pentax K1000 (SLR) with the standard 50mm f1.7 lens. It was really all I felt I needed and really all I even wanted at the time. Yes, I kind of was jealous of my friends who had the much more expensive Nikon SLRs, but I didn’t really see much need for the extra features. A fast 50 and a built in match needle light meter were basically all I thought any “art photographer” needed. Sure, I could see that journalists and wedding photographers would need more, but that was never my calling and I never found the Pentax lens to be lacking either–it got the job done.

Fast forward to now and I have a lifetime of buying selling and collecting and shooting all kinds of cameras. Because, other than being an avid photographer, I am also a pathological camera collector. The two sides of this seem to be opposed to each other, but perhaps they aren’t. While shooting many different cameras can get in the way of getting to really know one well, in the big picture, all cameras have a lot in common, so there are things you can learn no matter what camera you are shooting.

But back to exploring the concept of one camera, I’m trying to push myself into concentrating on shooting the Leica IIIf (pictured above). How I ended up with this camera was kind of a stroke of fate, so if there is something to the idea of “what is meant to happen is what happens,” then maybe I should just go with it. To set about finding the one camera would be very daunting, since there are so many to choose from, having one dropped in your lap, almost as if from the Gods, makes the choice a lot easier.

Before the end of my marriage and the financial calamity that followed in its wake, I was mostly shooting Canon Pro bodies, L-lenses, and their stellar TS-E lenses, along with a small kit of Leica R gear (for manual work). But in the eight years it took me to dig my way out of this crippling financial debt, pretty much all my belongings of value were sold off… all the Canon L lenses, the Leica R, my large format gear, and a modest Leica rangefinder kit (Leica IIIc with some lenses). I wasn’t that drawn to the old Barnack rangefinders back then, especially for a user camera, even though it was hard not to appreciate their classic German design.

Even without any world class cameras left in my bag, I still managed to get by and kept going out shooting photos. I guess part of me also doesn’t mind using modest gear, even perhaps taking it on as kind of an enjoyable challenge (“I don’t need no stinkin’ Leica to take good photos!”). One night when I took my kids to Bookman’s (a local used bookstore) I spied the Leica IIIf (shown above) from across the store poking out of a completely thrashed case. Once it registered what it was, I almost broke into a run across the store to make sure I was the one who got their hands on it first! Once I saw it up close, I knew what it was and was almost afraid to turn it over to look for the the price (Bookman’s is known for sometimes being ridiculously overpriced!), but to my surprise, it was only $25! Yes, the shutter curtain was cracked and the lens pretty much frozen up, but it was all there! $25! This is almost that once in a lifetime find that all junkers and collectors dream of!

It took a number of years to get back on my feet financially, but when I did, I sent the camera in to Youxin Ye and he fixed everything for what I thought was a really fair price. Everything works perfectly now. Just a joy to hold and and shoot! Smooth and silent!

Even though I had sold my Leica IIIc during my bankruptcy fire sale, I did keep a few lenses for the camera for some reason. None of them worth that much at the time, but from the only roll of film I shot with the Voigtlander and a set of photos that I had enlarged from this roll to be included in a local group show, I had the sense that the low production Color-Skopar was somehow special.

Industar-26M, Voigtlander Color-Skopar, and Jupiter-8 LTM Lenses

Besides the Voigtlander lens, the other two are low end Russian lenses. The first, the Industar-26M is predecessor to the often praised Industar-61 L/d, both very good performing f2.8 lenses. The second, the Jupiter-8 is a Zeiss Sonar copy. I wish I could say it was a stellar bootleg of the legendary Zeiss lens, but it’s pretty soft and pretty low contrast. My son liked adapting it to his Micro Four Thirds camera for a while and shooting it wide open for the effect, but while I can be a “bokeh snob,” I’m not really a fan of razor thin depth of field anyway, so other than just having a fast prime for the camera, I doubt it will get much use.

I came on the Color-Skopar as kind of a fluke reading about it online and seeing a closeout sale price of around $239. It seemed like an interesting LTM lens at a bargain price. While my Leica IIIf sat in my camera case unusable, the Voigtlander sat in a drawer completely orphaned by the lack of body to use it on. During this time I watched used prices of the lens soar, now somewhere between $500-600!

Everything I’ve read explaining the rise in prices points to a nearly cult following of the lens among Japanese photographers. If you look for examples from the lens on flickr or similar sites, they do feature a lot of (really nice) work by Japanese photographers. American photographers seem to be more drawn to the extremes in lens design–super fast apertures and biting sharp resolution. To my eye, many modern lenses are too sharp. Giving a too “clinical” look. And as I’ve already said, super narrow depth of field is not at all my thing either. I always read that the Japanese have a different sense of aesthetics than most Americans and I think I can it appreciate it as well. My shared appreciation for this Voigtlander lens fits in with this. While the character of the lens is somewhat subtle, there is something to its rendering properties that I really love, and besides that, it works really well on my IIIf! Pairing the old with the new!

Voigtlander Color-Skopar on a Leica IIIf

So between the Elmar collapsible lens both making the camera fully pocketable and giving a classic older lens rendering, the Color-Skopar giving the camera the ability for more modern, but still distinctive look, and the Jupiter-8 for more “artsy” wide aperture work, the camera can be used for many types of photography.

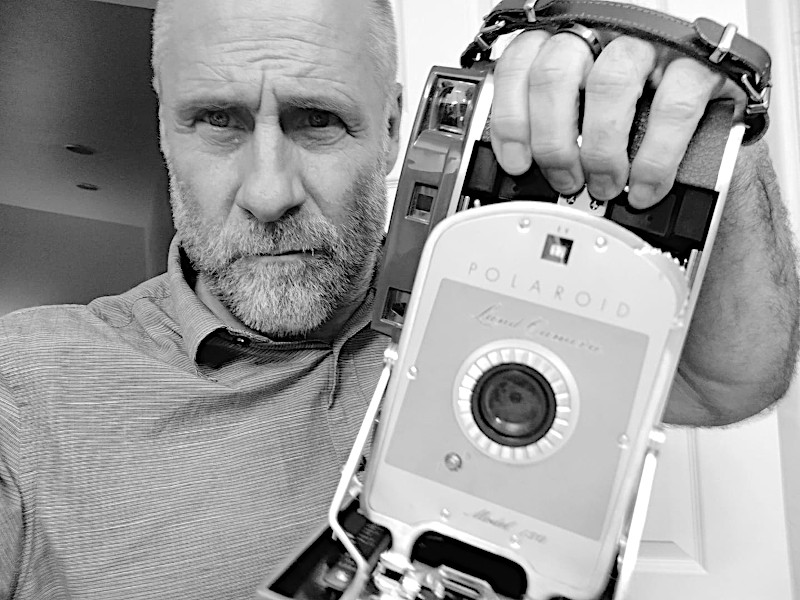

And what’s really the point of this all? For me it’s to have fun, so in that vein, below is a photo of me goofing around with the camera!

Me With My Leica IIIf

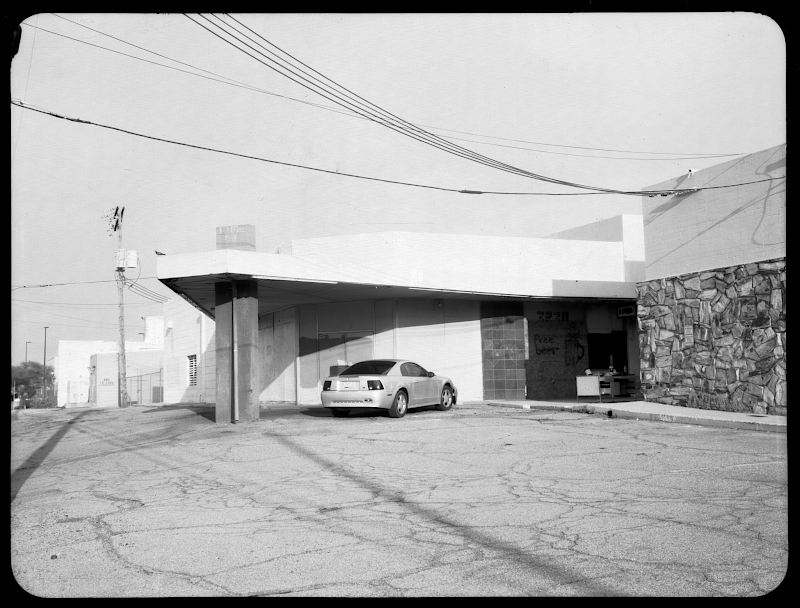

I’ve been taking the Model 150 Polaroid Land Camera out with me when I’ve been shopping and doing errands. You never know when you will find an interesting environmental emotional study that needs to be captured. Once thing I like about shooting sheet film cameras with paper is that you can shoot a single image and then quickly develop just that one image without much effort. Here are a few recent shots taken with my modified Polaroid Camera on Fomaspeed Variant 311 RC paper and developed in Tmax 1:9. Many people claim this paper is super fast (for paper) and can be exposed as ISO 25 or 50. I’m finding that the best I can do is ISO 6 at midday and ISO 3 in the late afternoon (including a yellow filter).

When Mark Zuckerberg’s AI machine did its magic, it pushed an ad for this old Polaroid Model 150 camera into my news feed. They somehow knew this was another camera priced and packaged just right for me and that I wouldn’t be able to resist buying it. I paid $30 shipped for it along with a what turned out to be a very beat up and worthless leather case and some original documents. I like having the original documentation.

In case you aren’t familiar with these cameras, it is slightly upgraded version of the original entry level Polaroid Land Camera. The main difference is that it has a built in rangefinder. Production was begun in 1957 and these were sold until 1960. These used the original and long discontinued Polaroid (Type 42) roll film.

The Model 110’s were the professional versions of this camera and while being essentially identical, they have a much better Rodenstock Ysarex f4.7 Lens in a Prontor shutter (or similar depending on the exact model). The 110 cameras can be found for under $100, but they often go for much more and they still need to be modified to be used with any film available today. Maybe if I find a deal on one, I’ll give it the same mods, but very quickly, I think I’d rather put my money toward replacing the Speed Graphic camera I was force to sell a while back.

The Model 150 is equipped with a quality f8.8 triplet lens and I suspect that stopped down it performs nearly as well as the Rodenstock on the 110A.

I first remember seeing one of these cameras in the 1970’s. It was already so retro looking that I fell in love, but even then, the film was hard to locate and really too expensive to mess around with creatively (for me).

Over the last few years, I’ve noticed people converting these cameras to either take 120 roll film or 4×5″ film holders. Neither is really ideal since the 4×5″ conversions require extensive modifications to the camera which unless you have a modest machine shop, end up looking too ragged for me. The 120 conversions require adding some kind of winding knob, and even then, if done cleanly, the native 3×4″ image size is larger than 120 film will cover. Other approaches entail using the camera as-is, but loading film or paper into the camera in complete darkness and only taking a single shot. This final approach seems much too limiting to me.

But after getting this beautiful camera into my possession, I decided I would be able to come up with perhaps a better way to modify it for actual use.

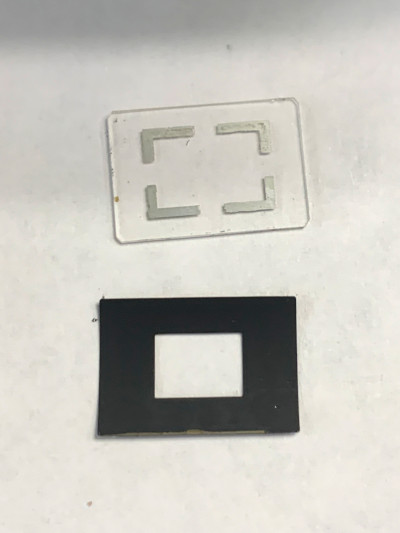

My solution was to design my own single sheet 3.5×5″ film holders. I used simple black card stock from Michael’s and since I’ve been experimenting with paper negatives, that is what I’ve been using in the camera (though there isn’t any reason I can’t load my film holders with 4×5″ sheet film cut down to 3.5×5″).

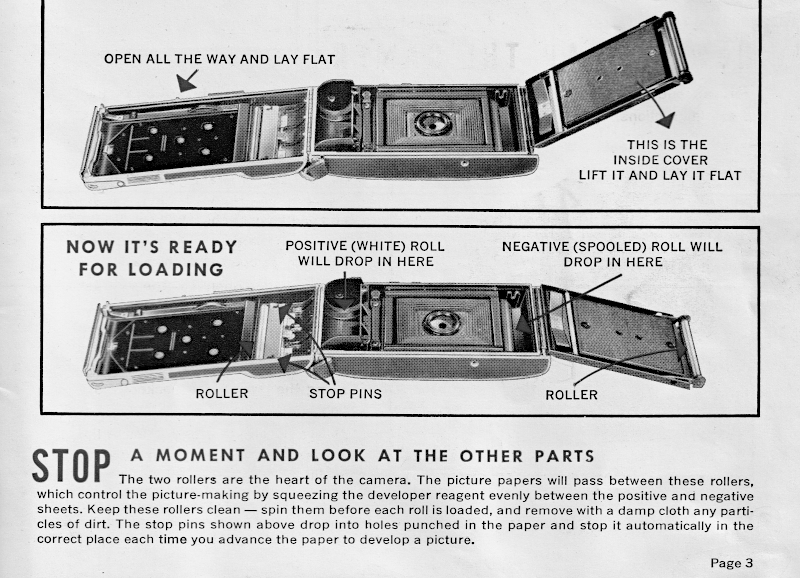

As shown in the user manual below, you can see that there is both an inner back (with pressure plate) and an outer back (left hand side). My goal was to leave the camera looking as original as possible, at least on the outside.

To allow for a film holder to be placed in the camera, I first recognized that the inner back needed to be removed. I did this by removing the wire from the hinge and then using a pliers to snap off the raised lip on the camera where the hinge was riveted onto the it. This was easy to do very neatly because of dramatic step in the thickness coupled with the cheap alloy metal used in the camera body.

I then took the inner back and used a hack saw to cut off the hinged end of it. After popping out the two rollers, I was able to wire the roller flanges together and use two sided foam tape to attach the old inner back to the outer back (as seen on the left hand side above). The pressure plate is now in the correct location for holding down my slim film holders. I cut a piece of 1/8th inch hobby ply to cover the Negative Spool well and hot glued it in place (upper right hand side). This allows the existing silver spring (upper left hand end) to push down the film holder against the flat surface. After suffering light leaks in my first tests, I lined this surface with black felt as a light trap.

I also added a thin wooden strip to act as a stop for the film holders on the other side of the film gate. Below you can see how the film holders fit right into the back of the camera.

When you close the back of the camera, just a short end of the film holder and dark slide stick out the end where you would originally have pulled out the film. With these film holders, you simply pull out the darkslide and the camera is really to shoot. Shoot your image, reinsert your darkslide, open the back and put in a new film holder and you are ready for your next shot.

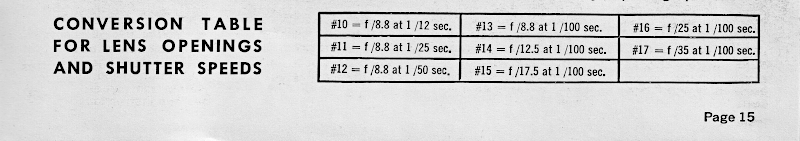

The camera uses an EV system for setting exposure. The user manual lets you know what aperture and f-stops are used for each EV number. If you flip the I->B switch on the front of the camera you get a single shot in “bulb” mode for long exposures. The camera takes universal cable releases.

From my first two test shots, light leaks were a big problem, but the images still looked pretty promising. The shot below was taken handheld at EV = #10. This test shot alerted me to the need for better light seals in the camera and to add an additional siding black ring to better seal my film holders. This shot was taken with a yellow cloud filter on Ilford MGIV glossy RC paper developed in Kodak Tmax developer (1:9).

After the first tests, tweaking the camera and film holders, I moved on to try a new paper that people on the internet were recommending–Fomaspeed Variant 311 glossy. Since I tend to like Foma film, I was happy to try their paper. Plus it’s cheap!

Both shots below were taken at f35 and 1 second exposure (midday), essentially rating the Fomaspeed paper at ISO 6 (including the filter factor for the yellow cloud filter). Contrast was well controlled, but the negatives were so dense that I will probably rate the paper at ISO 12 next time. With the low contrast, the paper seems to have pretty good latitude.

The camera is a total beauty and while even rather simple, it is quite capable. I tested the rangefinder and thankfully it was perfectly accurate so I didn’t have to open up the top of the camera to adjust it. The scale focus was pretty far off though, and the slots cut too short to correct, so I had to file them longer to correct this, but it was probably wasn’t necessary since the rangefinder is so large and bright that I can’t imagine myself not using it.

While the Model 150 is really too old to have had an impact on my life, I later discovered the old (newer) packfilm cameras like my Polaroid 360. Unlike shooting film (which I did a lot of when my kids were young) and shooting digital when it became affordable, there was always a magic for my kids watching me use the big packfilm camera and showing them real photos being developed right in front of their eyes. While Polaroids ushered in a new way of seeing and interacting with photographs, it is pretty much gone with the advent of digital photography.

If you are feeling nostalgic and would like to read about the history of Edwin Land, his inventions, the Polaroid cameras, and their impact on culture and society, I can’t recommend INSTANT, The Story of Polaroid, by Christopher Bonanos highly enough–a very enjoyable read.

For those wanting to do something similar, below are my notes for making the film holders. I’ve made five of them so far, they don’t take much effort, but they do need to be glued which means they take time between the steps.

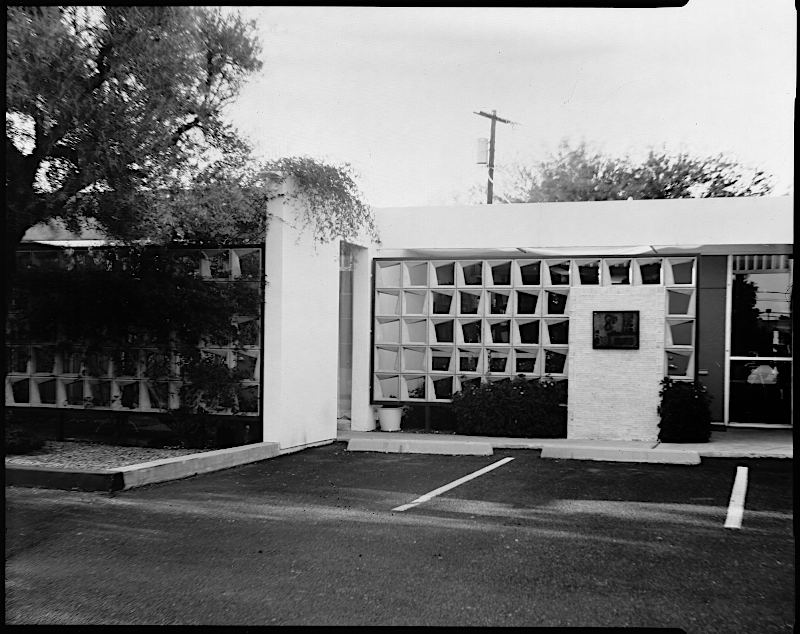

So I’ve taken out my Burke and James 4×5″ Orbit camera into the more urban setting. This time fitted with my Kodak Bausch and Lamb Rapid Rectolinear lens. It is much brighter than the Kodak meniscus lens and a bit sharper in the corners and edges, but still not exactly up to modern standards. Again, I was shooting Ilford MC RC paper rated at ISO 6 (developed in Kodak Tmax film developer). Of the four shots I took in this small office park, these three were exposed pretty perfectly. A fourth was under exposed and couldn’t really be rescued. It is quickly becoming apparent that paper negatives are very sensitive to any under exposure. I’ve been using my Sekonic Twinmate meter for all my shots to try and get more reliable exposures.

I’ve shot all these photos with the lens set to f32. Stopped down this far and shooting after 5:30 pm, gives very long exposures–these mostly around 4 secs. On a windy day, like this one, you can see a lot of motion blur in the trees and foliage. I think I like this effect.

Between the motion blur, the paper negative giving a more old fashioned orthochromatic film look (being mostly sensitive to blue light) and the hundred year old Rapid Rectolinear lens giving a less than sharp image from corner to corner, these photos have what I think is a somewhat unique (and might I add, “romantic”) look.